Poverty for demographic groups in the U.S.A.

- Alexis R. Santos-Lozada, PhD

- Aug 21, 2016

- 11 min read

Introduction

Differences in poverty levels among demographic groups are a pressing issue in the United States[1]. There is substantial body of literature that deals with exploring the causes of poverty among demographic groups in the United States. This report will present a brief overview of the history and causes of poverty for demographic groups in the United States.

Figure 1: Poverty Rate in the Continental United States

White Poverty

White poverty has existed in United States throughout American History, with higher poverty persistence in rural regions. The South has been identified as the home of the poor white population. Even though poverty rates for this group is significantly lower than those of the other race/ethnic groups in the US, they count of white population in the United States is higher than for any other group. White elites in the US have said the only reason for white poverty to exist, do not include social class, but a series of behavioral and noneconomic factors such as genetic defects, inbreeding and non-acceptable behaviors that include laziness and alcohol abuse. This notion can be traced back to colonial times where it was believed that all whites were benefited from slavery and those who were not benefited were either deficient un culture, racially impure or the product of incestuous relations.

The historical roots of White Poverty in the US can be traced back to colonial era when more than the half of white migrants came to the country to work as servants. Their servitude was in exchange payment of the passage to cross the Atlantic and a promise of land after repayment of the debt with the wealthiest individual. Due to lower life expectancy and life conditions, most of these persons died before they finished the repayment, returned to their country of origin or lived their life as landless citizens.

In the North, whites found opportunity in the emerging industries however these jobs did not carry guarantee of stability nor provided enough payment to live above poverty line. In the south of the United States, slavery became an impediment for whites finding sustainable jobs with high salaries. Since slavery made most of the labor unavailable for whites, they had to work as laborers, assistants, tenant farmers, mobile labor force in most of the time they were just supplying the demand of workers caused by shortages of slaves in the region.

White poverty was deepened because of the disenfranchisement resulting from the political transformations occurring before World War I. After the war the number of white poor reduced dramatically, but it continues to exist in the whole country and particularly in isolated rural areas of the South. These poor whites are referred as “rednecks”, “poor white trash” or “white trash”. These labels tend to enhance the prevalence of ignoring socioeconomic factors in the poverty outcomes of the individuals.

Figure 2: Poverty Rate for Non-Hispanic Whites in the Continental United States

African American Poverty

African American poverty is a lasting effect of slavery. Even though slavery was abolished in the US over a hundred years ago, the previous legal status of African Americans produced the rise in legal, political and economic disabilities even after the Emancipation Proclamation. In most cases African Americans were victims of segregation, discrimination and inequality, these factors affected their ability to access education systems, labor markets, housing and healthcare services. African Americans were victim of these conditions even if they moved out of the South where their effect was more patent. Residential segregation was the result of informal discriminatory housing policies that included negation of mortgages, at the same time this informal measures reduced the possibility of residential mobility for this group. After the transformations of all these conditions, African Americans continue to find themselves being poorer, dying younger, more unemployed, less protected by Health Insurance and less educated than their white counterparts.

Despite all the historical indicators of poverty persistence, African Americans have been excluded from social welfare systems. Clear examples include the Mother’s Pension Programs, the New Deal and the Social Security (initially). The federal government responded to the civil rights movements by declaring the War on Poverty, taking direct aim to solve the segregation problem and the consequences it brought for educational and employment opportunities. Policies approved by the government include the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965, Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, Elementary or Secondary Education Act of 1965 and the Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development Act of 1966 (Model Cities). These policies were designed to eliminate racial discrimination in employment and equalize economic opportunity for this and all minority groups. In terms of employment Bellinger and Wang (2011) have found that grocery stores are less likely to be located in highly populated African American zip codes, thus reducing the availability of jobs for African Americans in the US. A proportion of African Americans have made some improvement in their living condition. Black Middle class grew since 1970’s, producing better conditions for those who achieved it.

There is strong opposition to programs that aid African Americans in the US, some have called for a complete elimination of the welfare structure of the country. The program that is mostly targeted by these attacks is the one that provides income support to single mothers and their children. Culture and media have stigmatized African Americans structural poverty (existent also for Non-Hispanic Whites) as racial misbehavior. These attacks on welfare policy drove the welfare reforms efforts of the 1990’s which led to the replacement of Aid to Families with Dependent Children with the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program (TANF).

Anti-welfare forces have declared the need to end welfare, but there is still need for income support, job creation policies and other antipoverty programs. These programs tend to have small effect in the structural problem of poverty in African American population.

African Americans also face the problem of decline of blue-collar and manufacturing jobs, inadequate education institutions, and various public health crises (such as AIDS). Direct effects in the person security include inadequate taxing policies, diminishing resources, homelessness and impoverishment of the population as a whole.

The association of poverty with African Americans still produces popular hostility toward programs that aim to mitigate poverty. This has caused persistent disparities in the economic opportunity and well-being of Black and white population.

Figure 3: Poverty Rate for Non-Hispanic Blacks in the Continental United States

Latino Poverty (Hispanic)

This race/ethnic group is the first one that does not tracks their significant presence to colonial history. The presence of Latinos in the US has two main origins: (1) the annexation of additional territories to the union and (2) migration from South America to the US. Poverty in Latino population are as varied as the group but the major causes include immigration patterns, dependence of low-wage occupations, low levels of education, poor English proficiency, discrimination and limited training programs and good educational facilities.

Data available about Latino families’ economic situation is precarious; this is even considering the benefit of the 1990s economic boom, which sent the poverty rates to the lowest levels since the 1970s. The economic downturn of 2001-2003 and the subsequent economic depression of late 2000s increased unemployment rates among Latinos. Latinos are also victims of lower levels of education, which is one of the most important factors that explain poor economic outcomes among US Latinos. Vocational education and non-completing of High School limits the educational experiences of Latinos and predetermines their outcomes.

Latinos also lack English proficiency which is one of the main elements needed for social mobility. Capps, Ku and Fix (2002) found that English proficiency has a more significant effect than immigration status. Lack of proficiency has economic and social consequences, creating social isolation for individuals into groups and limits the resources and increases constrains. Training programs are rarely available in immigrants languages (Spanish), limiting the access to those programs. Migration status disables migrant Latinos ability to move up the economic ladder and they are forced to compete with new immigrants for the limited jobs at the bottom of the job scale.

Job opportunities for Latinos are mainly concentrated in low-skill jobs in agricultural, service, construction, craft, repair and transportation sector. These jobs carry with them instability, high levels of unemployment, limited benefits, and low wages. As a result of these conditions Latinos have a lower proportion of full-time, full year jobs.

On top of the previously described situations; Latinos also face occupational segregation, lack of networks and face discriminatory practices in the labor market. This limits the ability of Latinos to access training programs, investment opportunities and promotions in their respective fields.

Figure 4: Poverty Rate for Hispanics in the Continental United States

Asian Poverty

Poverty among Asians is no independent from migration and the path Asians have followed to arrive to the United States. In part it has been influenced by the response of settled Americans to Asian migration, which has subsequently leaded to conditioned economic opportunities and economic security. Racism and nativism generate discrimination against Asian Americans; causes of this include differences of language and culture impairment which prevents them access to educational experiences.

As well as African Americans, Asians have been prevented from participating in welfare programs during the second half of the 20th Century. During the 1880s Asians were singled out as undesirables and were barred from citizenship in some states, they were negated education, jobs, and legal protection and even property rights. These laws were aimed to Chinese and Japanese immigrants. Racial discrimination for Asians also ended in 1965 with the approval of the Immigration Reform Act of 1965. A vision towards reunification of families increased the flow of Asians to the US.

After the 1965, Asian immigrants are very diverse in terms of socioeconomic background. The largest segments are those who benefited from the Family Reunification program. Some of these migrants ranged from population with considerable human capital and individuals with limited marketable skills. Other benefited from the Occupational Preferences Program, which seek to attract workers with high technical skills, high education levels and exceptional talents. These last groups have helped increase the amount of persons considered Middle Class in the country. Some are political refugees who fled Asia during the Vietnam War. From what has been presented previously, Asians are over represented at the top and the bottom of the labor market.

Poverty rates between Asians and Non-Hispanic Whites were comparable in the 1960s, under 18%. In the 1970s these rates were 10% for Non-Hispanic Whites and 11% for Asians. Since that period and during the 1990s; poverty rates have moved in a divergent way, as Non-Hispanic Whites have a rate of 9% and Asians face a 14% of poverty rate. At the end of the decade the poverty rates were four points higher for Asians when compared to Non-Hispanic Whites.

Asian American poverty is found in two types of enclaves. The first is the places known as Chinatowns which have been transformed by immigration into working-poor-neighborhoods. These enclaves depends mostly on tourism, it includes a hidden part of sweatshops. The jobs available pay low wages and offer few benefits, many of this working poor are only one paycheck away from falling into poverty. Elderly populations without pension benefits are big proportion of the population of these enclaves.

Apart from the Chinatowns, there are some communities established during the mid-1970s. These include places such as Little Saigon, CA. Others are economically depressed places such as New Phnom Penh in Long Beach, CA. These communities include over a third of adult population falling prey to unemployment and their main source of income is welfare benefits. Failure to include refugee population in mainstream economic society has led to these conditions. Welfare reforms from 1990s have presented obstacles to noncitizen participation in social programs from welfare to food stamps and even Medicaid. Poverty is devastating the Asian immigrants and Asian Americans. According to Ong (in Mink and O’Connor, 2004) states that Asian American poverty has not received adequate attention because of the enormous race/ethnic diversity of Asian population. Their small numbers do not give them sufficient political power. Poor Asian Americans are overlooked because of the prevailing perception of the success of Asians in the US as one of higher educational achievement and occupational success. Tragically the success of a few masks the economic hardships of 1 million Asian American.

Figure 5: Poverty Rate for Non-Hispanic Asians in the Continental United States

Poverty in Rural America

Historically and today poverty is more prevalent in rural America. The picture of Rural Poverty is much more different from Urban Poverty. Poor persons in Rural America face different macroeconomic circumstances and survival strategies than those living in Urban America. This makes poverty policies designed to impact inner city poverty less effective in Rural America. Family structure in Rural America have somewhat started to present the same trends found in Urban America, with single headed households which is increasing children poverty in this setting. Rural America has not been immune to the social correlates of poverty such as alcohol and drug abuse, domestic violence and homelessness; this is disturbing since attention programs and services are seldom available in rural America.

Figure 6: Poverty Rate for Metropolitan/Non-Metropolitan Counties in the US

Data

Data for this report come from the American Community Survey (ACS) 2006-2010 Summary File; the level of analysis is county. The value of using the five year rather than the one or three year estimates is that is contains data for all areas of the United States; it has a largest sample size, and reliability (Census, 2010). Additionally this dataset is better used when precision is more important than currency, and when used to analyze elements in small levels of geographies such as county.

This research will also incorporate Rural-Urban Continuum Codes for 2013. The Rural-Urban Continuum Codes form a classification scheme that allows distinctions between metropolitan counties based on population size and nonmetropolitan counties by the degree of urbanization and by adjacency to a metropolitan area. These codes will be transformed from their original nine classifications to a dichotomous Metropolitan/Nonmetropolitan classification scheme (UDSA, 2013).

Methods

Basic descriptive statistics and 95% confidence intervals for the mean are presented in Table 1. Additionally Z scored approximations produced using Wilcoxon Rank Sums Tests will be used to test for differences between poverty rates in Metropolitan/Nonmetropolitan areas of the United States, the results of these tests are included in Table 2. All statistical processes were completed using SAS.

Measurements

Poverty rates are calculated by dividing the total population who had an income in the past 12 months below poverty level over the total population for who poverty status is determined in the sample file (Table B17001001, ACS, 2010). Additionally this research incorporates poverty rates for Non-Latino White, African Americans, Latinos and Asian Americans.

Results

Table 1 presents basic descriptive statistics for the United States. As it can be appreciated poverty rates are higher for African American and Hispanic Population.

.

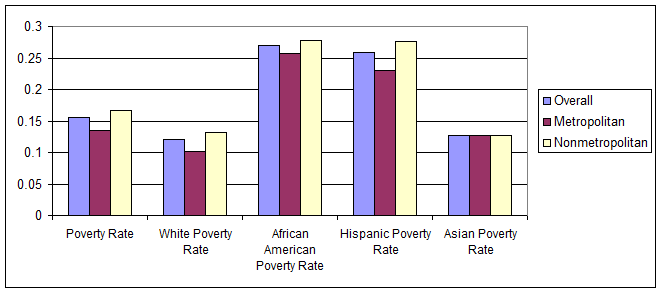

Table 2 includes descriptive statistics for Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan counties in the United States. It also presents chi-square statistics and significance levels for Wilcoxon Ranks Sums tests to test for differences between poverty rates in Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan counties in the United States. The standard deviations [1] for rates in Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan are not similar, with Metropolitan counties having lower standard deviations, a clear sign of lower variation between rates in the Metropolitan scenario. The results of the Z-score test, correcting for normal approximation indicate that poverty rates are significantly different in Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan counties in the US, with exception for African American Poverty Rates; partially supporting the findings of Jensen and Jensen, in Goreham (2008).

It can be appreciated in Figure 6 and 7, most of the highest poverty rates are found in rural areas, especially in the Rural Southern United States, at the same time poverty is found across the US-Mexico Border in the state of Texas.

Conclusions

Poverty for White and African American Groups in the United States has deep historical roots that can be traced until the colonial era. In the case of Latinos and Asians the poverty comes from their migration status to the United States as well as from individual characteristics such as language acquisition, migrant status, social isolation and work sector participation discrimination.

In the most part of the Poverty Rates presented in Table 2, poverty tends to be significantly higher in Nonmetropolitan counties when compared to the Metropolitan counties, except in the case of African Americans.

References

American Community Survey (2010). Summary File for 2006-2010: 5 year estimates, U.S. Census Bureau.

United States Department of Agriculture (2013). The 2013, Urban Influence Codes for U.S. Economic Research Division.

Bellinger, WK and Wang, J (2011). Poverty, Place or Race: Cause of Retail Gap in Smaller U.S. Cities. Review of Black Political Economy, Vol. 38, pp. 253-270.

Capps, R; Ku, L; and Fix, M. (2002). How are migrants faring after Welfare Reform? Preliminary evidence from LA and NYC. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Goreman, G (2008). Encyclopedia of Rural America: The Land and People. Volume 2: N-Z. Grey House Publishing.

Gwendolyn, M and O’Connor, A (2004). Poverty in the United States: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, and Policy. ABS-CLIO, Inc. Santa Barbara, CA.

United States Department of Agriculture (2013). Rural-Urban Continuum 2013 Codes. Economic Research Service. Retrieved from: http://www.ers.usda.gov/.

Supplemental Material:

[1] Demographic Groups Poverty Overviews are based on information presented in Gwendolyn and O’Connor (2004).

Comments